One week, two deals

Although the capitals of the UK and Europe saw a much-muted Christmas season, devoid of official events and fireworks, the lack of celebration didn’t mean that work wasn’t being done in the corridors of power. The last week of 2020 saw the EU agree trade deals with both the UK and China. Just a few weeks ago both deals seemed unlikely, but the year has been one of many surprises.

Four years ago, the UK unexpectedly voted to leave the EU. The vote illustrated clear divisions between the four nations of the UK and will have long lasting implications for the unity of the United Kingdom. For the past four years the issue of Brexit has been front and centre within British politics with the primary issue being whether the UK and the EU could agree a deal to manage their trade relationship as two distinct powers. The torturous history of those years will be chronicled and debated by historians for years to come but the net outcome is that a deal was done, it was good enough to avoid the worst possible outcomes of disrupted trade and travel and the pound strengthened to finish at the highest level of the year against the dollar at around 1.35 dollars to one pound. Before the vote four years ago the pound was trading around 1.5 dollars to the pound and had hit a low of 1.15 back in the depths of the first UK lockdown.

The agreed deal is only the end of the introduction to Brexit proper though. Although the UK formally left the political institutions a year ago the trade terms remained unaffected until the end of 2020. Now the UK really is on its own, just as the Brexiteers wanted, and the future of the British economy is far from certain.

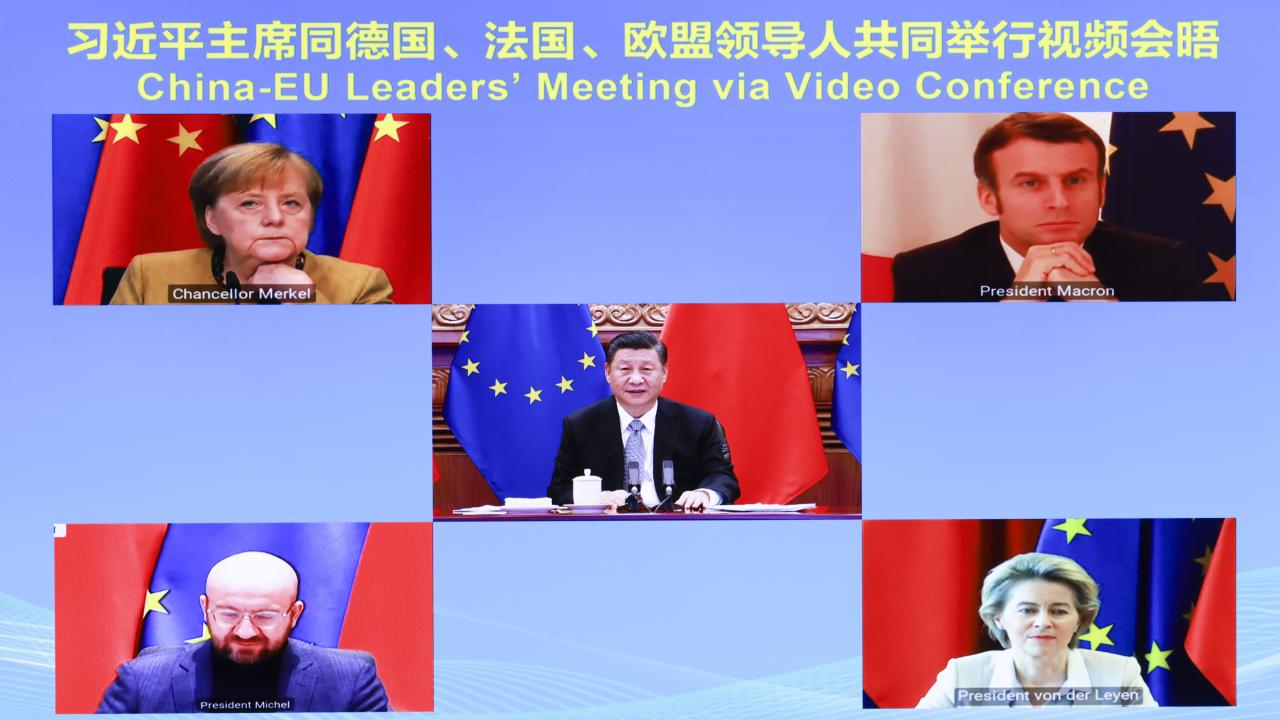

The second deal of the week was also unexpected. The Comprehensive Agreement on Investment between the EU and China has been 6 years in the making. It was seen as unlikely because of the requirement for meaningful change from the Chinese side when it came to market openness, support for state owned industries and labour rights. But German Chancellor Merkel had set 2020 year end as a self-imposed deadline to complete the deal. German industrial might drove this deal forward and the official EU communication posted online included the following sentence,

Participants welcomed the active role of the German Presidency of the Council, and of Chancellor Angela Merkel in particular, who has put special emphasis on EU-China relations and fully supported the EU negotiation with China.

While of course factually true, and perhaps just a mark of gratitude of the Chancellor’s support and drive this could also be read as placing the deal firmly at her feet if the relationship turns sour at a later date. Engaging with China to further trade must be a part of any future relation with China but the EU, by agreeing to such a significant deal now, has given away key leverage over China just as a new era of post-Trump relations start.

Dealing with China

Having avoided the worse possible Brexit outcome the UK needs to try and find a role in the world. The reality of EU membership was that the UK was a leading player within the group driving forward the single market and seen as one of the most business friendly and dynamic economies. Britain has now lost that influence and has seen its economy suffer one of the largest knocks of any developed economy due to the ongoing mishandling of the Covid-19 pandemic. When it comes to China policy the old pre-Brexit policy of David Cameron and the “Golden Era” of Chinese relations is well and truly over and should be referred to as the Golden error instead. Over the past year Britain has taken a surprisingly robust role when it comes to speaking up for Hong Kong. The most significant step was the commitment to offer a path to citizenship for over 3 million Hong Kong residents who either have or would be eligible for UK British National Overseas (BNO) passports. Such a bold approach was unexpected given the UK Government’s tough stance on immigration which was part of the Brexit philosophy. Needless to say, such steps have infuriated China and the pandemic travel restrictions have limited any global movement. It remains highly doubtful that China will allow so many to physically leave Hong Kong but the issuance of BNO passports is reportedly at all times highs.

With that in mind Britain may think it is open to the world but having a trade deal with China would seem remote without Britain having to roll back some of these policies and significantly tone down its language. Britain simply does not have domestic economic clout nor bring with it the EU economic clout as it charts a new path in a world dominated by trade blocs. That is not to say that Britain cannot play a global role, it remains at the top table of many world bodies starting with its permanent membership of the UN Security Council, it is a major funder of the WHO, has an impressive international developmental aid record, although it has been foolishly cut due to domestic pandemic concerns, its language, culture, and soft power remain substantial. London’s role as a global financial centre may still surprise as well. Although it has lost some of its access to Euro denominated products it cannot be assumed that any single European city can step into the breach. While Paris and Frankfurt would be expected to take over the role nothing should be assumed. Paris work culture is very different from London and the mayor of Frankfurt recently said the city didn’t want hordes of bankers coming to the city as it would just drive up house prices and worsen the traffic. Hardly a sign that the city is ready for a global role.

For the EU the situation is very different. Only 3 months ago this column looked at the EU’s attempts to get tough with China. Turned off by Trump’s approach and yet not fully understanding the nature of the China threat the EU was starting to take steps to frame China as a competitor and that the old engagement was not working. President-elect Biden has explicitly spoken about the need for democracies to come together to respond in a coordinated manner when it comes to China so the agreement of the long outstanding CAI appears to completely undermine those efforts just as the political environment shifts in the US.

Ironically as Chancellor Merkel was finalizing the trade deal the EU issued the following statement,

This was in response to the 4 year sentence handed down to Zhang Zhan whose only crime was to report on the pandemic outbreak in Wuhan. China has arrested numerous citizen journalists who reported about the true extent of the pandemic and the government failings but that has all been scrubbed from official versions now. Zhang and others are seen as troublemakers in need of punishment and correction. It was unlikely that Zhang’s plight received any attention in the call between Chancellor Merkel and General Secretary Xi.

The agreement of the CAI is not the end of the story, the European Parliament still needs to review the deal and the 27 members must agree it formally. That will take some months and will certainly throw up some robust debate. Across Europe, think tanks and China specialists expressed their reservations when it came to this deal, the end of 2020 deadline, was wholly self-imposed by Merkel yet the political and business elites were determined to push ahead with it. The deal itself cannot of course solve all problems when it comes to EU China trade, and the commitments made by China are hardly watertight. For those who have watched Xi China over the past few years this is a regime very much following its own path regardless of international commitments. The business lobby argues that this deal will put EU companies on a level playing with US companies and the commitments they achieved under the US Phase 1 deal, but the world has moved on from then. To conclude such a significant piece of legislation now, after 6 years of discussions reflects a willful blindness to China’s actions over the past year.

By agreeing the deal now the EU, whether it admits it or not, is sending a signal to China’s leaders that China’s early cover up and ongoing misinformation around Covid-19 doesn’t matter. That its introduction of the National Security Law in Hong Kong doesn’t matter. China ongoing boycott of Australian barley, coal, seafood and wine doesn’t matter. That China’s mask diplomacy during the pandemic doesn’t matter. The use of concentration camps and forced labour of the Uyghur minority doesn’t matter. The EU elites seem to think that economics can be neatly compartmentalized and be held distinct from those other issues but if nothing else the Australia example is the most telling. The economic dependency of Australia on China has become a liability not a benefit to Australia. The EU has already seen Norwegian salmon targeted in such a manner over the Nobel prize to Liu Xiaobo. China does not make the distinction between politics and economics; it has again and again used economic leverage to gain political advantage. Surely Merkel and others understand this. If on the other hand the rush is also to ensure that the new Biden administration don’t try and limit the EU in some way that too doesn’t seem to bode well for a more united front when it comes to China.

It is though unfair to think that the CAI is the be all and end all of trade deals which could have addressed all these wrongs. But at the same time the agreement as announced while advancing European corporate interests isn’t that game changing either. China has shown time and time again an incredible inventiveness and willingness to twist meanings to not comply with agreements it finds inconvenient.

China, in a surprise to most, has had a good year. Its harsh lockdown measures clearly limited the spread of the virus to allow it to return to broadly normal life well before most developed countries, its economy is growing again and its stock market has rallied strongly.

General Secretary Xi must be feeling very proud and confident as he looks around and sees the world flailing still. He isn’t so confident that he can accept any form of criticism of him or the party, nor is the economy so strong that it can ignore the growing defaults which are now affecting state owned enterprises as well as private companies or that it is only growing because of ever greater amounts of inputs. China’s pre-pandemic problems haven’t gone away nor been solved by the pandemic. To cap the year with the RCEP deal then a few weeks later the EU CAI shows that China still has tremendous economical pull. No one can or should deny that. Economic engagement with China is essential in today’s world but the EU has wasted leverage which it could have used better if it had waited. The engagement with China is far from over, the Biden Presidency will look very different to Trump and it is important that both the EU and the UK combine their efforts to face China. For all the perceived differences between the US, UK and EU there is far more that unites them than divides them. But Japan, Korea, Australia and India shouldn’t be ignored either. All these countries have common concerns and interests when it comes to China. A new chapter in China relations is about to start, cooperation and coordination of like mined democracies is essential.

カテゴリー

最近の投稿

- 個人の人気で裏金議員を復活させ党内派閥を作る解散か? しかし高市政権である限り習近平の日本叩きは続く

- トランプG2構想「西半球はトランプ、東半球は習近平」に高市政権は耐えられるか? NSSから読み解く

- 2025年は転換点だったのか?

- トランプのベネズエラ攻撃で習近平が困るのか? 中国エネルギー源全体のベネズエラ石油依存度は0.53%

- ベネズエラを攻撃したトランプ 習近平より先にトランプに会おうとした高市総理は梯子を外された

- Was this the Pivotal Year?

- 中国軍台湾包囲演習のターゲットは「高市発言」

- 中国がMAGAを肯定!

- トランプが習近平と「台湾平和統一」で合意?

- 中国にとって「台湾はまだ国共内戦」の延長線上