After 7 years of Russia’s “pivot to Asia” policy, the geopolitical landscape starts to shape a new bipolar order with Russia and China on one side versus the West led by the U.S. on the other. Although there are many problems between Moscow and Beijing, the confrontation with the “united West” brings them closer together and makes them ignore the problems in their bilateral relations for now. But this does not mean the issues that exist in their relations are going to disappear on their own.

The foundation of the relations

It will be a simplification to say that the confrontation with the U.S. underlies the blossoming partnership between China and Russia. In fact, there are existing building blocks that make it even necessary for China and Russia to have a good relationship.

As one of the best Russian China watchers Alexander Gabuev points out, there are at least three pillars that support the relations between China and Russia: staeity on the border, economic and political compatibility of the two systems.

First, China and Russia share one of the biggest land borders in the world and want it to be stable and secured. There were episodes of border conflicts in the history of the two countries and the territorial dispute between them was not settled until the early 2000s.

The second pillar is economic cooperation. The complementarity of structures of the two economies look like they are destined to get closer: Russia is the world’s biggest exporter of natural resources and China is the biggest importer.

The third pillar is the authoritarian approaches in both political regimes. Russia and China both are different types of autocratic hybrid regimes that oppose the classical Western approach to the governance model.

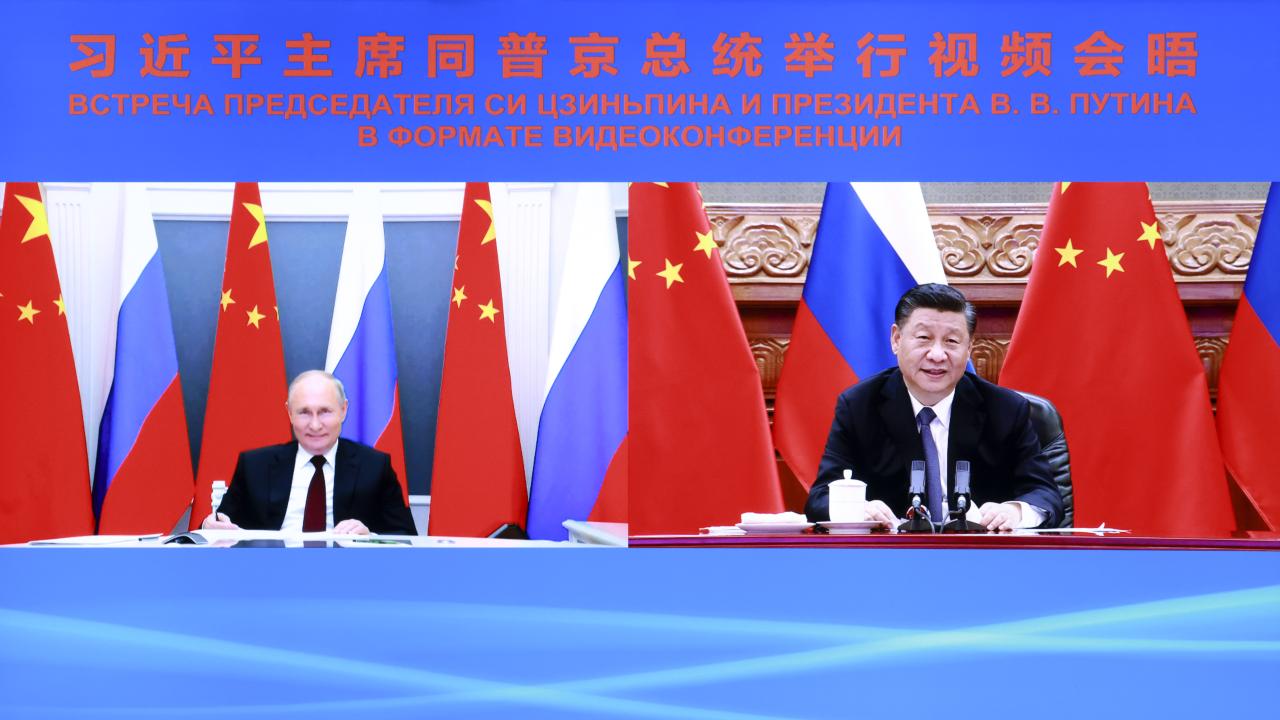

In other words, these are the objective reasons for the Sino-Russian rapprochement, and confrontation with the West is becoming another pillow that drives them closer together. The recent meeting of President Vladimir Putin of Russia and Chinese President Xi Jinping is just another example that proves this trend.

July 16 is an important date for the Sino-Russian bilateral relationship. This day 20 years ago Russian President Putin and his at that time Chinese colleague Jiang Zemin signed a Treaty of Good-Neighborliness, Friendship and Cooperation. The importance of this document cannot be underestimated because it sets the foundation upon which Beijing and Moscow were able to develop their relationship further.

In late June 2021, Putin and Xi met online to prolong the Treaty, although technically there was no need for such an event. The Treaty’s 25th paragraph goes “if neither side of the contracting parties notify the other in writing of its desire to terminate the treaty one year before the treaty expires, the treaty shall automatically be extended for another five years and shall thereafter be continued in force in accordance with this provision.”

However, this approach does not correspond to the spirit of the current state of the Sino-Russian partnership. Moscow and Beijing could not have missed the opportunity once again to demonstrate to the world how strong mutual understanding between the countries is. Especially, considering that in June President Putin had an in-person summit with U.S. President Joe Biden in Geneva.

Successes and problems

During the online meeting, Putin and Xi talked about the successes that their countries have managed to reach in recent decades. But a closer look at what and how been said during this event shows that the relations are asymmetrical and Moscow needs Beijing more than vice versa.

Take for example the speeches of the two leaders. President Xi Jinping was brief and talked for only 3 minutes, while President Putin talked for more than 7 minutes and brought a lot of examples that prove Sino-Russian friendship. Both leaders mentioned the 100th anniversary of the Communist Party of China but Xi Jinping did not mention the role of the USSR in its founding, although, in theory, Moscow as a legal successor of the Soviet Union would have been pleased to hear anything like that.

An important result of the meeting was the joint statement of the two countries. The 17-page (in Russian) document manifests all the main directions of the development of relations: from education and tourism to military cooperation. In this document it is visible that Beijing is taking the lead in shaping the narrative of the relations: Russia has adopted China’s concepts of the “community of common destiny” and “the new era of Sino-Russian relations” that is taken from Xi Jinping’s theory.

Other than that, the document highlights the main achievements of Moscow and Beijing in recent years. China has become the closest partner for Moscow in the whole Asia-Pacific region. On the political level, the relationship is at its historical peak.

Excellent personal rapport between the leaders is one of the drivers of the current relations: Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping call each other friends, celebrate birthdays together, award each other with medals, and drink vodka. China is a popular destination for the Russian president to visit (all in all Putin had 16 visits) and Russia is the most popular destination for the Chinese leader (Xi Jinping visited it 8 times). Both of the leaders understand each other well as they position themselves as strong rulers and have ambitions to go down in the history of their countries.

This personal relationship adds to intergovernmental politics. Russia is helping China to create a missile launch detection system, the two armies participate in the largest joint military exercise since Soviet times, Russian and Chinese long-range bombers conduct joint patrol missions, etc.

If the political and strategic cooperation is very close, the economic side of the partnership does not look so impressive. The total annual trade turnover although hit the record high has not come even close to those numbers that the leaders were pronouncing several times earlier. In 2019 the figure reached its highest level of $110.7 bln (because of the pandemic it fell in 2020 to $107.7 bln). However, 7 years ago it was planned to reach $200 bln by 2020. Now this plan is rescheduled by 2024.

In a joint statement, the parties did not mention any achievements in the field of investments. The amount of FDI from PRC to the Russian economy has not really changed since 2014 according to the Russian Central Bank data (fluctuated around $2-3 bln). At the same time, Chinese Ministry of Commerce data claims that from 2014 to 2019 the amount of FDI stock from PRC to Russia grew from $8.7 bln to $12.8 bln. Even under a heavy sanction regime Russian economy still relies on the investment flow from the Western countries: at the beginning of 2021, the FDI stock from Germany amounted to $18 bln, $38 bln from the Netherlands, $32 bln from the U.K., etc. Partly this is the problem of Russian statistics that ignores offshore schemes in which end investors are Chinese but appear as from the Bahamas or Cyprus in official statistics.

But while looking at major Chinese investments in Russia, it’s obvious that all the flagship bilateral projects exist outright thanks to thanks to the support at the highest political level, out of strategic considerations. Most of them are focused on energy and are implemented by state giants such as the CNPC and Sinopec petroleum corporations or the Silk Road Fund. There are exceptions to this rule but the amount of investment coming via these independent sources cannot be compared to the state-supported ones.

Business-to-business relations between countries are also full of problems. Russian corporations and businesses are not allowed to export to China a big chunk of their products because of the protectionist policies of the PRC, they also have difficulties with expanding their business to the Chinese market. At the same time, Chinese companies face resistance and anger when they come to Russian markets. E.g., before the pandemic Russian airlines were mad at Chinese rivals for headhunting Russian pilots. Some businesses in Russia even complain to their government when they cannot stand the rivalry with Chinese businesses: there were cases in a tech industry and taxi.

These are not the only problems that exist between the two biggest political partners of Eurasia. And even all of these issues do not seem to be an obstacle that is big enough to stop Russia and China from getting close together. Big geopolitical events like the Ukrainian crisis of 2014 and the COVID-19 pandemic even accelerate a wide-ranging set of processes and incentives inside both Russia and China that are helping pull the two largest Eurasian powers toward each other.

United approach towards the West

Another factor driving Russia and China closer is their respective suspicion about U.S. long-term intentions. The United States officially considers both China and Russia as its geopolitical competitors and has accused both countries of interfering in its internal affairs.

America’s relations with Russia have never been stably good. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union Russia was willing to become a part of the Western part of the geopolitical arena but never fit in. Its political regime and super-power ambitions of the current policymakers made it almost impossible for Moscow to join the club of U.S.-led democratic states.

In parallel China was also expected by the U.S. sooner or later to join its club. The idea in Washington was that political freedom would follow new economic freedoms in China and that its economic growth would have to be built on the same foundations as in the West. However, this did not happen and now we are witnessing China that not only does not want to follow the Western model of governance but creating its own.

Finding themselves in an opposition to the global trend of democratization creates a special bond between Moscow and Beijing. And the pressure from the West becomes a natural reason for Russia and China to bolster their ties.

The official description of the state of the relationship has changed for the last several years. For a long time after Moscow and Beijing avoided using the word “ally” in regard to each other until recently when in October 2019 at the Valdai International Discussion Club President Putin for the first time named Sino-Russian relations with a special term: “This is an allied relationship in the full sense of a multifaceted strategic partnership.”

China continued to avoid the term, preferring something like “all-encompassing partnership and strategic interaction.” However, in the recent joint statement, the two countries highlighted that their relationship is not just an outdated alliance but more than that: “While not being a military and political alliance, such as those formed during the Cold War, the Russian-Chinese relations exceed this form of interstate interaction. They are not opportunistic, are free of ideologization, involve comprehensive consideration of the partner’s interests and non-interference in each other’s internal affairs, they are self-sufficient and not directed against third countries, they display international relations of a new type.”

These are not just words; they have a practical manifestation. Moscow and Beijing do not let ideology take over the relations which makes the partnership more pragmatic. As one of the best experts on Russian foreign policy Dmitri Trenin puts it, the formula of the current Sino-Russian relations: “we’ll never be against each other, but we do not always have to be with each other”. This means that although Moscow and Beijing share some common interests in international relations, they are not bound to act in certain ways because of the high-level partnership that they have.

There are many examples of that pragmatism. E. g., China does not support or criticize Russia’s policy toward Ukraine and Crimea. Beijing has been silent towards the status of Crimea after 2014 and Chinese businesses continue sending delegations there. Moscow on its tern does not want to be dragged into China’s territorial disputes in the South China Sea, so it will not have to choose between China and Vietnam that became the first non-post-Soviet country to join the Russia-led free trade zone of the Eurasian Economic Union. Similarly, Russia does not take sides in the Chinese Indian border clashes, as it values India as one of the biggest importers of its weapons and military machinery.

Lessons from each other

Another important trend in the relations between China and Russia is that they are actively learning from each other on different issues. In domestic policy, China has been paying interest to Russian know-how in controlling the NGOs, and vice versa Moscow looks carefully at China’s successful example of total control over the Internet.

In the foreign policy domain, both countries share a desire to shape the international order in a way that places sovereignty and limits on foreign interference in domestic affairs at its heart. This is visible in debates on various areas of global governance such as norms in cyberspace and control over the Internet, etc.

There is a shared desire to change the global order that in the mid-XX century, as Chinese and Russian leaderships believe, was designed by the U.S. and other Western countries without Moscow’s or Beijing’s active participation. And now for Moscow but especially for Beijing, it seems unfair that the world as a whole mainly lives by the rules that Western democracies came up with almost a century ago.

Russia and China sometimes act similarly in the global arena. The tougher tone that Chinese diplomats like Zhao Lijian are called “wolf warriors” for to some reminds Russian MFA spokesperson Maria Zakharova who for the last 6 years in her position appeared at the center of numerous diplomatic scandals.

Chinese media also look at how Russian media corporations like “Russia Today” or “Sputnik” operate and spread a certain narrative across the globe. Similarities in the approaches of China and Russia can be spotted also in the digital domain. Chinese actors carefully study the Kremlin’s tools of digital propaganda like online trolling and disinformation campaigns.

There are also other forms of more classic cooperation between China and Russia. For example, both states as permanent members of the UN Security Council support each other during voting and setting the agenda. However, this is all done separately and the actions of the two states are still intuitively led and not coordinated.

When it comes to the confrontation with West China and Russia show their unity and put aside the debates. However, some misunderstanding in the relations exists. In some areas, China is becoming an uncontested economic partner for Russia. In addition, Beijing’s growing power raises its influence over Central Asian countries–the region that Moscow considers its “backyard” but does not have enough resources to invest in especially during the pandemic. China becomes the main source of aid for the region and that together with the growing dependence of the local elites on financial flow from China shifts the fragile balance in Central Asia towards Beijing and could lead to friction with Moscow.

Circumstances make Russia and China come together much faster than it would be comfortable for the two countries and their societies. There is still a high level of mistrust of each other on both sides of the relations and the situation will get even more complicated as Moscow does not have many options.

カテゴリー

最近の投稿

- Old Wine in a New Bottle? When Economic Integration Meets Security Alignment: Rethinking China’s Taiwan Policy in the “15th Five-Year Plan”

- イラン「ホルムズ海峡通行、中露には許可」

- なぜ全人代で李強首相は「覇権主義と強権政治に断固反対」を読み飛ばしたのか?

- From Energy to Strategic Nodes: Rethinking China’s Geopolitical Space in an Era of Geoeconomic Competition

- イラン爆撃により中国はダメージを受けるのか?

- Internationalizing the Renminbi

- 習近平の思惑_その3 「高市発言」を見せしめとして日本叩きを徹底し、台湾問題への介入を阻止する

- 習近平の思惑_その2 台湾への武器販売を躊躇するトランプ、相互関税違法判決で譲歩加速か

- 習近平の思惑_その1 「対高市エール投稿」により対中ディールで失点し、習近平に譲歩するトランプ

- 記憶に残る1月