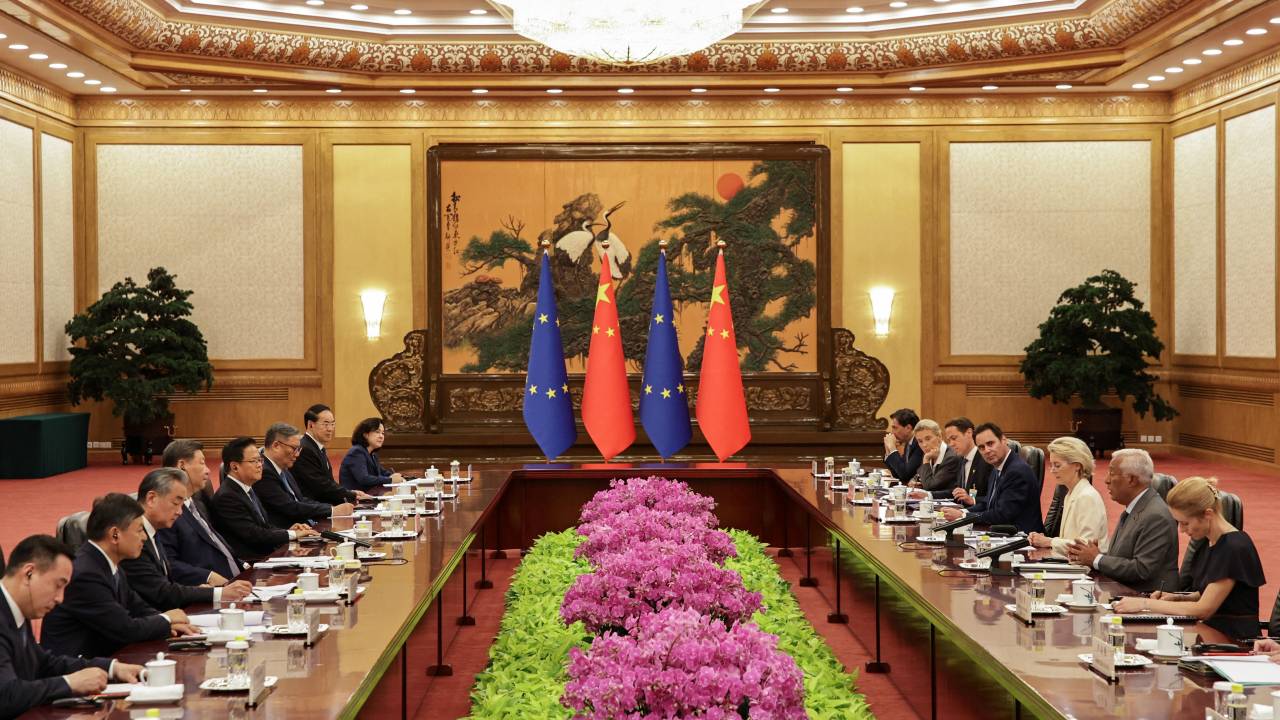

The air in Beijing on July 24, 2025, will be thick not just with the summer humidity, but with an almost palpable tension as European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and European Council President António Costa sit down with Chinese President Xi Jinping and Premier Li Qiang for the EU-China summit. This isn’t a routine diplomatic encounter; it’s a critical juncture marking 50 years of diplomatic ties, though overshadowed by the chaos of geopolitical seismic shifts of the recent years.

The discussions are set to be focused on trade imbalances, China’s alleged role in enabling Russia’s war economy in Ukraine, human rights concerns, and the overarching shadow of an increasingly unpredictable United States under a re-elected President Donald Trump. Far from a celebratory anniversary, this summit will be a stark reflection of the EU’s delicate balancing act, caught between its aspiration for strategic autonomy and the compelling realities of a complex and uncomfortable world.

The Evolution of EU-China Relations

For decades, the West’s and (the European Union’s in particular) approach to China was largely characterized by a strategy of engagement, driven by the belief that economic interdependence would foster political convergence and integration that would eventually bring democratization to the PRC. China was primarily seen as an economic partner, a vast market for European goods and a crucial link in global supply chains. However, this perspective began to shift, slowly at first, then with increasing momentum, particularly in the latter half of the 2010s. The turning point was arguably epitomized by the EU’s 2019 designation of China as simultaneously a ‘cooperation partner,’ a ‘negotiating partner,’ an ‘economic competitor,’ and, crucially, a ‘systemic rival.’ This multi-faceted labeling signaled a profound re-evaluation of the relationship, acknowledging the competitive and rivalrous aspects that had become increasingly prominent.

The impulse for the new stance can be traced to several factors. First, China’s increasingly state-driven economic model, characterized by widespread subsidies, intellectual property theft, and discriminatory market access practices, began to directly impinge on European businesses and industries. European companies faced significant barriers to entry and unfair competition within the Chinese market, while Chinese firms, often state-backed, enjoyed relatively unfettered access to the European single market. This growing asymmetry in economic relations fueled calls for a more level playing field.

Second, China’s assertive foreign policy and more repressive domestic policy, particularly its crackdown in Hong Kong, and the human rights abuses in Tibet and Xinjiang, increasingly clashed with the EU’s core values and its commitment to a rules-based international order. While the EU historically sought to compartmentalize human rights concerns from economic engagement, the sheer scale and systematic nature of these issues made such a separation increasingly untenable.

Finally, and perhaps most significantly, the growing Sino-American rivalry played a pivotal role in shaping the EU’s strategic thinking. As the US, under several administrations, adopted an increasingly confrontational stance towards Beijing, treating it as a primary strategic competitor, Europe felt natural to follow along and the concept of “decoupling” from China, initially championed by Washington, prompted a nuanced response from Brussels.

In March 2023, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen introduced the concept of “de-risking” as the new organizing principle for the EU’s China policy. This strategy, distinct from “decoupling,” aims to reduce excessive dependencies and mitigate strategic vulnerabilities in key sectors, without severing overall economic ties. As articulated by von der Leyen, “It is neither viable—nor in Europe’s interest—to decouple from China. Our relations are not black or white—and our response cannot be either. This is why we need to focus on de-risk—not de-couple.” The rationale behind de-risking stemmed from lessons learned during the COVID-19 pandemic, which exposed Europe’s overreliance on China for essential goods like medical supplies, and from Russia’s weaponization of energy supplies following the invasion of Ukraine, highlighting the dangers of dependence on a single partner.

De-risking involves a multi-pronged approach: strengthening the EU’s own industrial base and competitiveness, diversifying supply chains to reduce reliance on any single country, and using economic security tools to protect against coercion and unfair practices. This has led to increased scrutiny of Chinese investments in critical infrastructure, stricter export controls on dual-use technologies, and trade defense instruments such as the ongoing anti-subsidy investigations into Chinese EVs, the moves that China has read as protectionist and responded to with its own investigations into European products.

Trump’s Return

The return of Donald Trump to the White House has introduced another layer of complexity and uncertainty to Europe’s geopolitical landscape, directly impacting its calculus on China. Trump’s MAGA-foreign policy, characterized by transactional diplomacy, a propensity for tariffs, and a questioning of long-standing alliances, has generated considerable apprehension in European capitals. His previous administration’s aggressive trade tactics demonstrated a willingness to prioritize perceived national economic interests over transatlantic solidarity.

Under Trump, the US’ approach to its allies has often been seen as unpredictable. This creates a dilemma for Europe: how to align with a key security partner whose foreign policy direction could shift dramatically without warning? The prospect of renewed transatlantic trade wars, or even a weakening of NATO commitments, forces Europe to consider a more independent foreign policy stance. This does not necessarily mean an embrace of China, but rather a greater emphasis on Europe’s own strategic autonomy and resilience.

The current geopolitical environment sees Brussels caught between two significant pressures. On one hand, Washington continues to push for a more unified front against China, particularly on issues related to technology competition and human rights. On the other hand, Trump’s actions threaten to erode the very transatlantic unity that such a front would require. As a result, some European leaders are contemplating whether the EU should “reset” relations with China, out of a pragmatic need to minimize struggles in a highly volatile international politics.

The EU’s recent actions, such as targeting Chinese banks for facilitating trade with Russia as part of its latest sanctions package, demonstrate a growing confidence and unanimity in Brussels to confront Beijing on certain issues. This newfound resolve is noteworthy, given the historical reluctance of some member states to challenge China directly for fear of economic repercussions. However, this resolve is tempered by the understanding that a complete break with China is neither feasible nor desirable, especially given Europe’s reliance on China for critical minerals and magnets essential for modern technologies, as well as its own ambitious green transition goals.

Europe’s Hopes and Beijing’s Ambitions

What does Europe hope to achieve in its relations with China now? The EU’s current approach is a delicate balancing act, aiming to minimize struggles by getting along with Beijing in areas of shared interest while being ‘proactive’ in defending its interests and values where they diverge.

On the economic front, Europe seeks a more level playing field. The EU is concerned about its chronic trade deficit with China, which was 300 billion euros ($350 billion) last year. Brussels wants to see greater market access reciprocity for European companies, an end to discriminatory practices, and a reduction in Chinese industrial overcapacity, particularly in sectors like EVs and solar panels, which threaten European industries. The EU is also keen to secure concrete concessions from China on ensuring reliable access to rare earths and critical minerals through unrestricted export licenses, as these are vital for Europe’s green and digital transitions. While no major breakthroughs are expected at the summit, EU officials hope China might at least acknowledge these concerns and take steps to stimulate domestic demand or address imbalances. The threat of reciprocal measures, as seen with past actions against Chinese EVs and the ongoing investigation into dairy products, serves as a subtle hint of Europe’s willingness to act if its concerns are not addressed.

Beyond economics, Europe aims to engage China on global challenges where cooperation is indispensable, most notably climate change. Despite the tensions, both sides are keen to showcase their green credentials. There were hopes that the July 2025 summit might yield a joint declaration on climate, although its materialization remains uncertain. The EU also seeks China’s cooperation on reforming the World Trade Organization (WTO) to ensure a more fair and predictable global trading system.

From China’s perspective, the primary objective in its relationship with Europe is to prevent the EU from aligning too closely with the US, particularly as US-China tensions continue to escalate. Beijing understands the level of disagreement in the transatlantic alliance at the moment and will try to broaden the potential wedge between the EU and the US.

Economically, China aims to rescind or delay EU sanctions and tariffs targeting Chinese products and it also wants to address European concerns about its industrial overcapacity and state subsidies, though it often frames these as legitimate aspects of its economic development. China’s lifting of sanctions on some members of the European Parliament, while largely symbolic, signals a desire to improve relations and create a more conducive environment for economic cooperation. Ultimately, China seeks to buy time and use dialogue as a means to soften the EU’s trade defenses and prevent further deterioration of economic ties.

Geopolitically, China wants Europe to acknowledge its narrative of multilateralism and to implicitly endorse its vision of a global order, one where China plays an increasingly influential role. Beijing also seeks to minimize international criticism of its human rights record and its policies in Xinjiang, Tibet, and Hong Kong, often dismissing such concerns as internal affairs or Western interference.

The Russia Factor

The war in Ukraine has profoundly reshaped the global geopolitical landscape, including the EU-China relations. While China has officially maintained a position of neutrality, its state of affairs with Russia after 2022, especially its continued economic and diplomatic support for Moscow have deeply troubled European capitals. EU officials now openly state that a significant percentage—estimated at 80 percent—of dual-use items used by Russia in its war effort originate from China. Brussels has repeatedly criticized Beijing’s continued export of components which are crucial for Russia’s military machine.

The EU’s frustration with China’s stance on Ukraine is palpable. Just days before the current summit, the EU sanctioned several small Chinese banks for facilitating trade with Russia, a move that Beijing has condemned and threatened to retaliate against. While Brussels does not expect a major shift in Beijing’s “no-limits partnership” with Moscow, it hopes for modest steps, such as tighter customs and financial controls on dual-use goods. The war has underscored Europe’s vulnerability to geopolitical shocks and the interconnectedness of security and economic interests.

China, for its part, views Russia as a strategic partner in countering perceived Western hegemony, particularly that of the United States. Beijing’s foreign minister, Wang Yi, reportedly told Estonian Foreign Minister Kaja Kallas that China does not want Russia to lose the war, fearing that the US would then shift its full focus to China and Asia. This perspective highlights China’s strategic calculus: keeping Russia afloat, even under Western sanctions, helps divert US and European attention and resources away from the Indo-Pacific, where China’s own ambitions are growing.

The Ukraine war has reinforced the EU’s determination to reduce dependencies and build resilience, not just in economic terms but also in its security posture. The conflict has highlighted the dangers of relying on external powers for security and the need for a more unified and robust European foreign policy. While some member states, like Hungary and more recently Slovakia, continue to pursue closer ties with China, the overall sentiment in Brussels leans towards a more cautious and assertive approach.

The war has also demonstrated the limits of China’s “neutrality” and its willingness to support a rules-based international order when its own strategic interests are at stake. This has led to a deeper skepticism in Europe about China’s commitment to global norms and its role as a responsible stakeholder. The EU cannot afford to sever ties entirely, given its economic interdependence and the need for China’s cooperation on global issues. However, the war has undeniably accelerated the EU’s “de-risking” efforts and reinforced the understanding that China, while a vital economic partner, is also a systemic rival whose actions directly impact European security.

Pragmatism and Resilience

The EU-China summit on July 24, 2025, will not be a turning point, but rather another step in a complex and increasingly challenging relationship. Europe is no longer under the illusion of a smooth convergence with China. Instead, it is grappling with the realities of a systemic rivalry that permeates economic, technological, and geopolitical spheres. The “de-risking” strategy, while a nuanced alternative to outright “decoupling,” signals a fundamental shift towards greater resilience and strategic autonomy.

The unpredictable foreign policy of President Trump further complicates this equation, forcing Europe to hedge its bets and invest more in its own capabilities. While the EU will continue to seek pragmatic cooperation with China on global challenges like climate change and pandemic preparedness, it will do so with a heightened awareness of the risks and a firm resolve to defend its interests and values. The “Russia factor” serves as a constant reminder of China’s geopolitical alignment and the potential implications for European security.

The coming years will see Europe navigating a perilous tightrope. Its success will depend on its ability to maintain internal unity, to articulate a coherent and robust China policy, and to build strategic alliances with like-minded partners around the world. The goal is not to isolate China, but to shape the terms of engagement in a way that promotes European interests, upholds international norms, and safeguards the future of the rules-based international order. This will require unwavering determination, diplomatic dexterity, and a clear-eyed understanding of both the opportunities and the profound challenges presented by China’s rise in an increasingly fractured world.

カテゴリー

最近の投稿

- 記憶に残る1月

- 高市圧勝、中国の反応とトランプの絶賛に潜む危機

- 戦わずに中国をいなす:米国の戦略転換と台湾の安全保障を巡るジレンマ

- トランプ「習近平との春節電話会談で蜜月演出」し、高市政権誕生にはエール 日本を対中ディールの材料に?

- NHK党首討論を逃げた高市氏、直後に岐阜や愛知で選挙演説「マイク握り、腕振り回し」元気いっぱい!

- A January to Remember

- Managing China Without War: The U.S. Strategic Turn and Taiwan’s Security Dilemma

- 「世界の真ん中で咲き誇る高市外交」今やいずこ? 世界が震撼する財政悪化震源地「サナエ・ショック」

- 中国の中央軍事委員会要人失脚は何を物語るのか?

- 個人の人気で裏金議員を復活させ党内派閥を作る解散か? しかし高市政権である限り習近平の日本叩きは続く