Stimulus as last

A month ago this column discussed the opacity of the Chinese economy. What was really going on with the Chinse economy as data was suppressed and secrecy and suspicious became the norm. What was clear though, and what partly explained the clamp down on data and public discussion was that the economy was weak, and the government growth targets for the year were unlikely to be met. Not that the Chinese government is reading or responding to the few words written here but by the end of September the government via the central bank, the PBOC, announced a major monetary stimulus which many in and outside of China had been hoping for, and for which the government has defaulted to time and time again. Whenever there is economic weakness or an external knock such as the GFC there is an expectation that the government will step in, but the continual question over the past year has been why the government hasn’t acted to boost the economy. They now have done so but is it what is needed? And what is the stimulus going to do?

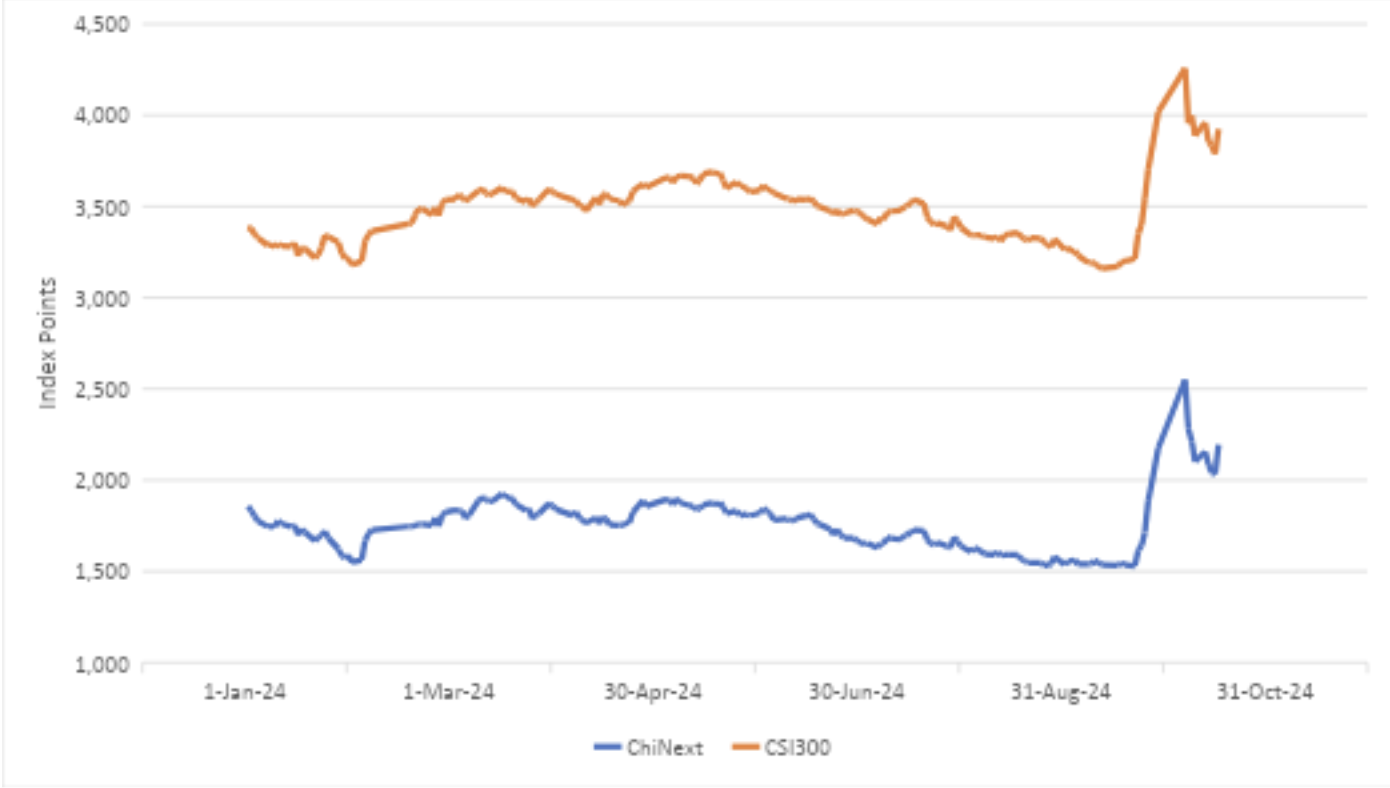

The most visible sign of the stimulus was seen in the stock market. Having trended down over several years and seen a huge outflow of foreign funds, within a few days the market soared over 30%. This is the most violent rally in the market’s history as over 3 trillion RMB of stocks were traded in a single day. On one day the Shanghai Exchange effectively stopped trading as the system was overwhelmed with orders. This is not so much reflective of the large retail investor base in China but shows how China, like other markets, has become dominated by computer driven trading which when the market signal flash the computers can flood the market with orders. But a weak market was a symptom of the poor economy not the cause of it. The market’s seemingly irrational reaction was really very rational within the Chinese context. The PBOC stimulus announcement was monetary not fiscal, the PBOC was pouring money into financial assets. The reserve requirement ratio was cut, interest rates and mortgage rates were cut, and 800 million RMB was explicitly allocated to buy stocks! How could the stock market not go up on such news? Further measures were announced to help ease local government debt burdens which have accumulated via Local Government Financing Vehicles, LGFVs. These are not new problems, and the announced measures are only an extension or broadening of already existing programs. At first glance the scale of the support is impressive running into trillions of RMB, yet LGFV debt is estimated to be around 100 trillion RMB, that is the approximate size of the entire Chinese economy. The great irony here is that the proliferation of LGFV comes from the great Chinese stimulus of 2009 following the global financial crisis. Then to cushion the very real impacts from an imperiled global economy Chinese authorities turned on the credit taps and embarked on a spree of road, rail and infrastructure building. But while the policy came from the center it was up to the provinces and local authorities to actually fund the stimulus hence the rise of the LGFV.

The monetary stimulus failed to be followed up by any substantial fiscal stimulus which then led to dramatic reversals of the market after the long October National Day holiday. The market has held most of its recent gains and the announcement of third quarter growth coming in at only 4.6% still saw market rally by the expectation that more will be done in the final quarter to achieve the 5% growth number and an announcement of even more measures for non-bank financial institutions to buy more equities. This is an incredibly short-sighted way to approach the economy. China’s obsession with focusing on economic outputs instead of ensuring good economic inputs results in such knee jerk policy. Boosting the market, which is actually very easy, just buy shares, but it does nothing by way of a wealth effect for the average middle-class China who has most of their family wealth in property not in stocks. Nor does it drive any significant change in economic performance by the companies. Admittedly part of the stimulus measures was PBOC help for local governments to buy up unsold housing stock but even then, the scale of the problem is tremendous, the respected Enodo Economics estimates that Chinese unsold housing stock could house the whole population of Brazil. This is the result of a GDP target, not a market, driven economy.

Year to date performance of the CSI300 and ChiNext indices

Source: WIND Information

What does the stimulus tell us?

The first thing the stimulus reminds us of is that the government certainly has the capacity to simply throw a lot of money at issues which it considers important. That is not to say that the government isn’t constrained in a range of ways, but it can certainly direct large amounts of money when it wants to. This is what the indices reflect of course but it will bring adverse consequences in due time as well. The importance of central government institutions simply cannot be understated, that seems obvious in a one-party state, but it has become ever more significant in Xi’s China. As many of the provinces and local governments have seen funding dry up as the property market has slowed, they simply are not in a position to drive investment. That coupled with dramatic slowdowns in both domestic and foreign investment, whether it be in direct factory and manufacturing investment or private equity investment funding new companies, all eyes turn to the central government for support.

With the focus on significant monetary policy with much vaguer promises of fiscal investment indicate that the government is more interested in short term virtue signally type of measures. By driving such a short-term jump, followed by just as sharp a correction, grabs headlines, makes corporate owners richer on paper, but doesn’t tackle the problem of strengthening the real economy. For years the government has tried to discourage bubbles in both the stock and property markets, with the Xi mantra being that property is for living in not for speculation, yet the announced measures only seek to revive speculation in both markets.

Of course, further fiscal measures could still be announced and perhaps the government will indeed reach the 5% target for the year. But perhaps the correct response to that is a shrug of the shoulders and a “so what?” Few investors are looking at the GDP growth rate in China anymore as a measure of the viability of an investment. Geopolitics plays as great a factor as any. The past week’s market gyrations have played out against the biggest naval encirclement yet of Taiwan. The Taiwan issue is as big a concern to many investors as slight variations in the growth rate. Come early 2025 the government might be able to tout that the growth rate was achieved but it seems a poor use of their resources.

Voting with their feet

This column has always tried to give a broad picture of issues surrounding China and not to be too focused on the economy. That would be especially true nowadays as regardless of the growth rate there is no doubt that China has entered a period of significant lower growth than under the first two decades after WTO entry. Geopolitics has clearly taken on more importance under Xi Jinping, not just because of Taiwan, and aggressive behaviour in the East China and South China Seas, but also because of Xi’s globalization with Chinese characteristics under the belt and road initiative and its no limits friendship with Russia.

While the macro and country level concerns are always important it should never be forgotten that any nation is ultimately the collection and activity of millions of individuals and families and because of that individual activity can often point the way to bigger trends which are lost in the macro economics or high politics of running a nation. It is interesting to juxtapose the slowing economy in China with how a growing number of Chinese are responding to the slow down and the increasing personal restrictions within Xi’s China. It is not news to report on Chinese moving their money abroad, often illegally given the harsh capital controls in place. Overseas Chinese have driven prices in selective cities across north America and Australia for years. Having an overseas apartment or house or sending your child overseas for an education and then employment to ensure a green card has been going on for decades. What is now happening, or at least has become much more prominent is how Chinese are looking to Japan as often as the US as not just an investment location but place to relocate to and live. Jack Ma is the most prominent Chinese entrepreneur to have made Tokyo a second home, but you don’t need to be a billionaire to want to get out of China. In the past few years Singapore has been able to attract many Chinese who are looking for a familiar Asian environment with strong private property protections and well beyond the reach of the CCP. America still remains a draw for many but the rise in the number of Chinese trying to smuggle themselves across the southern border is remarkable. Thirty years ago, it was desperate young men being smuggled into the US by snakehead gangsters in search of work but now even the middle classes are trying to get in and they bring their children with them. A similar illegal network is starting to emerge in Europe as well. Europe is no stranger to illegal immigration although traditionally it has been African, and Middle Eastern migrants who are coming for economic reasons or to escape war. Although the numbers remain small, a few hundred per year at present, Chinese can travel to Bosnia without a visa and from there can try and get into the EU proper. There are no detailed statistics of the who is coming and why, but reports tell of people just wanting to get out of Xi’s China. The level of intrusion and surveillance of lives, and the state’s willingness to clampdown and imprison those who disagree with it has meant that whether growth is 5% or 10% there is a growing body of Chinese who want out and are voting with their feet. The Guardian newspaper recently cited the UN refugee agency which recorded over 130, 000 asylum applications from PRC nationals last year, a 5-fold increase from when Xi came to power. This outflow isn’t just minority groups who have come under broad societal repression, but this increase is being driven by the majority Han Chinese who too are feeling the squeeze of the one-party state.

Whether it be to tower blocks and glitzy homes of Tokyo or Singapore, or via the jungles of central America, or the mountains of southern Europe, more and more Chinese nationals are wanting to build their lives away from Xi Jinping’s China. The rejuvenation of the Chinese nation is not something they want to be a part of. It is tempting to play a numbers game and say that these people form only a small part of the population and don’t matter, but that would be the wrong lesson. No country just empties out, only a fraction of the population can ever leave, but what we see again and again in China is that those who have benefited most from China’s rise, or those who are educated, socially engaged and who can make a real positive contribution to the society are the very ones who are planning and executing an exit. Understanding the economy and analyzing government policy and response is an important topic but it is more important not to lose sight of what those who make up the economy are actually doing. In China, more are looking to get out and build their futures outside of Xi Jinping’s China.

カテゴリー

最近の投稿

- 習近平の思惑_その1 「対高市エール投稿」により対中ディールで失点し、習近平に譲歩するトランプ

- 記憶に残る1月

- 高市圧勝、中国の反応とトランプの絶賛に潜む危機

- 戦わずに中国をいなす:米国の戦略転換と台湾の安全保障を巡るジレンマ

- トランプ「習近平との春節電話会談で蜜月演出」し、高市政権誕生にはエール 日本を対中ディールの材料に?

- A January to Remember

- Managing China Without War: The U.S. Strategic Turn and Taiwan’s Security Dilemma

- 「世界の真ん中で咲き誇る高市外交」今やいずこ? 世界が震撼する財政悪化震源地「サナエ・ショック」

- 中国の中央軍事委員会要人失脚は何を物語るのか?

- 個人の人気で裏金議員を復活させ党内派閥を作る解散か? しかし高市政権である限り習近平の日本叩きは続く