Moral Hazard

Moral hazard has been a problem in Chinese capital markets since they were founded. Basically, the idea is that the government will always be there to orchestra a bailout of a failing company who can’t pay its debts, the government team will step in to buy stocks if they fall too much or the regulator will look to change the rules or limit new issuances to relieve pressure on a weak market. This underlying idea has meant that investors have never really had to properly price risk and rely solely on corporate fundamentals because the government has their back. Assumptions about the strength of that government support are being sorely tested with the shambolic performance of Ministry of Finance owned financial heavyweight Huarong Asset Management.

The moral hazard argument though can be stretched too far. In the stock market such faith in government intervention hasn’t stopped spectacular busts after just as impressive booms. Yet for over 20 years the stock market regulator has turned on and off the new issuance approval tap in direct response to the secondary market sentiment and market directions. The response to the collapse of 2015 saw a very broad range of measures from banning negative news stories about the market to outright state buying of tens of billions of dollars across over 1,000 different companies. In the bond market the assumption has always been that any given borrower just won’t default, in times of trouble there will always be some workout and the investor, especially the retail investor will always be made good. That didn’t mean that state companies, even central SOEs could borrow at the same rates as the government, there was always some spread over the government bond issuance but there simply wasn’t any expectation that default was a real concern across any part of the corporate issuance space, and certainly not for those names which sat directly under the state umbrella. The higher coupon on non-state bonds was to compensate for lack of liquidity and poorer tax treatment rather than a risk weighted calculation of default risk. For private companies the higher rates often reflected the limited borrowing channels available to then as the banking system traditional catering primarily to the state owned enterprises. This problem was understood by the authorities and the development of rating agencies was partly intended to rectify the issue yet all that happened was that most bonds and issuers end up with AA or higher grades, not surprising as companies could be restricted from issuing or buying bonds if they weren’t rated AA. That then led to corruption across the industry with payments made to ensure the company received the required rating.

Rating and moral hazard didn’t really matter much at the turn of the century. The only major issuers were the Ministry of Finance and the state-owned development banks but now the interbank bond market lists over 40,000 different fixed income securities from thousands of issuers across a wide range of maturities. The old ways simply do not make sense anymore. Not that China has been insulated from defaults, there has been a gradual build up of defaults over the past five years or so. How could there not with so much debt in the system and a slowing economy? But although many companies got into trouble and failed to repay their debts there was no clear approach to which companies would or would not get state help. The early model that state companies always would be bailed out and private companies would not was appealing but wrong. A local private company which employed thousands of workers was sure to have the local mayor doing what he could to ensure the company remained solvent.

But the concerns around Huarong aren’t just another possible default story, it is wrong to lump Huarong along with Luckin Coffee, Kangde Xin, Sino Forest or even Anbang and think of this as yet another of the long list of frauds and overstretched companies which appeared with regularity during the reform era. The problems with Huarong go to the heart of the Chinese financial infrastructure and show how moral hazard and the abuse of state support has become a millstone around the economy’s neck.

Huarong- financial royalty

Huarong Asset Management started over 20 years ago. It was founded as the partner bad bank to ICBC as part of the sector wide restructuring of the effectively broken state-owned banks. Very simply Huarong, funded by the central bank would buy the bad debts of ICBC and look to sell, restructure or otherwise dispose of the bad debts over the following decade. ICBC in the meantime would be free to regrow its business but starting with a much cleaner balance sheet.

Huarong’s ongoing role was not as prominent as the good banks yet ownership by the Ministry of Finance and a central role in the ongoing bad debt clean up made Huarong financial royalty within China. Directly connected to the very top but not the crown prince, perhaps a near cousin or younger sibling. Huarong made full use of its government ownership and implied guarantee and grabbed every opportunity to expand its financial footprint. Instead of being a special purpose vehicle specific to the bank clean up the company took full advantage as Chinese economy boomed to expand into new business beyond bad debt management. After ten years its bonds were rolled over into the far future and it eventually listed in Hong Kong in 2015. Throughout this time, it touted its distressed debt credentials, and its balance sheet grew and grew as did its headcount which made closing it down doubly difficult. Huarong was a company out of control, it had built up balance sheet assets of over 250 bn USD, it issued over 50 bn USD of debt and its Chairman Lai Xiaomin was executed earlier this year for corruption after tales of dozens of apartments, mistresses and literally rooms piled with cash. Investors had plenty early warning signs that the company had gone off piste.

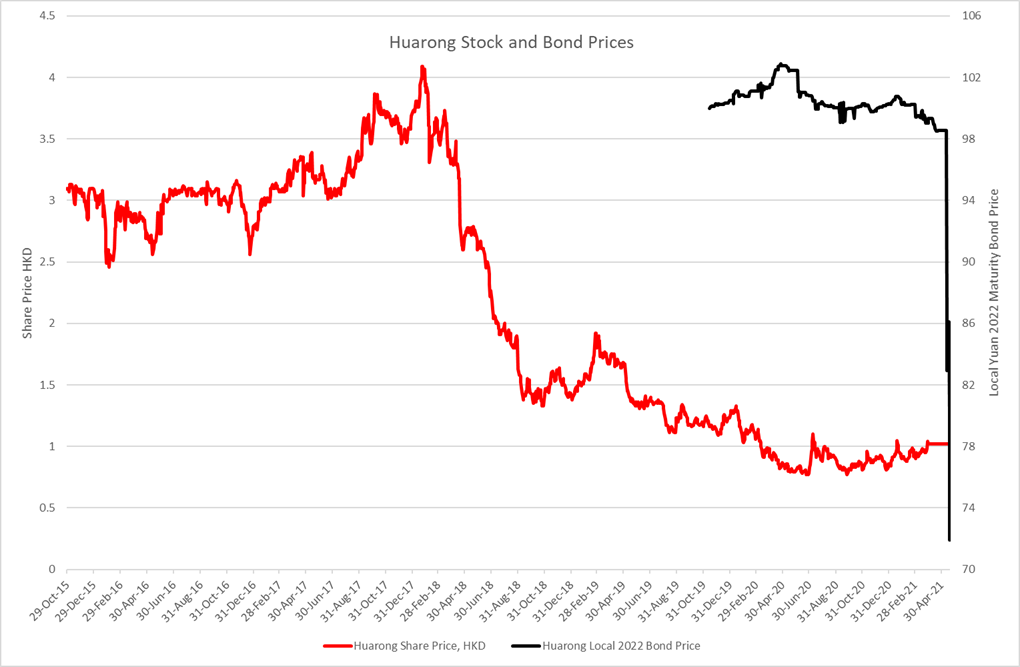

The current crisis stems from Huarong’s repeated failure to issue its 2020 annual report as required to do so under its Hong Kong listing requirements. This resulted in its stock being suspended from trading having fallen 67% since it listed in late 2015. The company has around 22 bn USD in offshore bonds and they have collapsed in value as rumours swirl whether the company will be able to repay. The New York Times even reported on a possible restructuring of the debt which would see both offshore and onshore bond holders nursing losses.

The below chart shows the stock price since listing and the recent performance of the onshore bonds.

Source: WIND Information

The vast amount of debt, coupled with the years of mismanagement and dreadful stock performance already worried investors. But even with missed reporting deadlines and stock trading suspended the Chinese government, the direct owner of Huarong was worryingly slow to voice its support for the company. If there was ever a company where a state guarantee was fully expected it was Huarong: a key player within the financial infrastructure, headquarters in the very center of the financial district and owned by the Ministry of Finance. Default was never entertained by investors. Support when it did come was late and weak. Statements that the company could pay its debts and that the company was operating normally is hard to believe when it can’t even produce its annual reports.

The Bigger Concerns

At the time of writing the fate of Huarong is still far from clear. In the past few years there have been plenty of examples of corporate failures and government intervention to rein in wayward tycoons. There have been SOE bond defaults and even the highly unusual move to bankrupt a (small) bank. But it seems inconceivable that Huarong will suffer the same fate even though the bonds have collapsed in recent trading (it should be noted that the bonds are highly illiquid meaning that prices can be volatile). The stock may find itself delisted and non-state shareholders cashed out but a bond default or restructure effectively means the state is defaulting. That is not to imply that Huarong doesn’t deserve to default, its business model was flawed from the start, it invested and lent recklessly and in any other market the bonds would have been written off as junk long ago.

What message is Beijing trying to send the market with their approach to Huarong. The moral hazard problem needs to be addressed but does Xi Jinping and his financial chiefs really want to let such a prominent entity default, even in a limited way? China has built up vast domestic debts since the global financial crisis. The numbers are staggering. The banking sector assets are nearly 50 trillion USD in size or approximately 3.5 times the size of the economy. Local government debts run into the trillions as do the still largely unregulated and off balance sheet wealth management products. Debt directly attributable to the central government, such as MOF bonds, policy bank bonds and Ministry of Railway bonds is still approx. 60% of GDP yet the that balloons to over 300% of GDP when all the implicit government guarantees are added in. The entire debt and banking system are built on the belief that the central government will stand good. If Huarong fails, then where does that leave provincial and local governments whose very existence depends on debt financing to survive and fund their budgets?

This sorry episode is worth putting in a larger context. To some commentators China it has become inevitable that not only will China’s economy overtake the US in absolute size but that the Chinese yuan will displace the US dollar as the world’s primary reserve currency. Huarong’s travails surely put pay to the second of those ideas. For the yuan to rival the dollar it would be essential that China remove capital controls and let markets decide the value of currencies and default risk. If China was to simply walk away from Huarong, or at least let bond investors no longer believe in a government guarantee then the entire market would rerate and the spectre of capital flight would again hang over the financial system. There is no way that a single party dictatorship like the CCP is ready to accept the vast flows of capital, and panic that would come with such poor decision making from financial leaders if capital controls were not in place.

There is then the question of signaling to the global market because this is a global story. Is Huarong guaranteed by the state? That should not be a difficult question to answer, and indeed a decade ago the answer would clearly have been yes, of course. But now, the answer is more like, yes, we think (and hope) so. Why has a vast state entity been unable to provide year end statements? Why has the government taken so long to provide any meaningful statement clarifying the situation or indeed not acted sooner when the company was clearly in trouble. Is this paucity of information and failure to communicate really what the world expects from the issuers of the world’s next reserve currency? Of course it isn’t. The Chinese Communist Party and the financial leaders in China are not ready to engage with the world in an open and direct fashion.

Huarong is a failed company operating a failed business model. It should have lasted 10 years and been wound down with any losses still outstanding being written off by the state. Instead Huarong and other asset management bad bank managers were allowed to expand into all sorts of financial businesses for which they were not qualified. They used their perceived state guarantee to issue vast amounts of debt which could never have been repaid. It is a very modern Chinese tale of financial mismanagement underpinned by the state’s unwillingness to write off bad debts and let the market allocate capital based on economic fundamentals. China’s economic growth has been impressive over the years but the financial foundation of its rise are indeed fragile. The weaknesses have been known for many years; it is only now that they are hitting at the heart of the financial infrastructure.

カテゴリー

最近の投稿

- 習近平の思惑_その1 「対高市エール投稿」により対中ディールで失点し、習近平に譲歩するトランプ

- 記憶に残る1月

- 高市圧勝、中国の反応とトランプの絶賛に潜む危機

- 戦わずに中国をいなす:米国の戦略転換と台湾の安全保障を巡るジレンマ

- トランプ「習近平との春節電話会談で蜜月演出」し、高市政権誕生にはエール 日本を対中ディールの材料に?

- A January to Remember

- Managing China Without War: The U.S. Strategic Turn and Taiwan’s Security Dilemma

- 「世界の真ん中で咲き誇る高市外交」今やいずこ? 世界が震撼する財政悪化震源地「サナエ・ショック」

- 中国の中央軍事委員会要人失脚は何を物語るのか?

- 個人の人気で裏金議員を復活させ党内派閥を作る解散か? しかし高市政権である限り習近平の日本叩きは続く