This article is a special contribution by Kazunari Shirai, Director of Global Research Institute on Chinese Issues

If coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is already in a pandemic phase, the response by the Japanese national and local governments seems to have come too late. While it is certainly better than nothing at this stage, the spread of this virus probably cannot be contained. Things should temporarily settle down in Japan as the monsoon season arrives, but the spread will not stop elsewhere and the spread will restart from autumn.

The main differences between COVID-19 and other seasonal infectious diseases are that the former has “a high infection rate” and is caused by “an unknown virus.” China should have swiftly disclosed information and contained the outbreak but failed because it prioritized preserving the status-quo. Thereafter, some countries and jurisdictions such as Taiwan, Hong Kong and Macau forced through stricter responses. However, while many countries such as Japan and South Korea understood the threat, they failed to initiate responses because of priorities given to short-term tourism demand and political considerations, as well as “normalcy bias”. In the end, countries were unable to implement coordinated responses, and the world is getting caught up in a pandemic. This situation is identical to the prisoner’s dilemma. It tells us that humanity’s short-sightedness is no match for Nature’s threats.

The essence of this problem lies with the economy.

The coronavirus threat has drastically reduced global demand and severed supply chains originating in China. In a pandemic, people would prefer to stay indoors and save up rather than spend it. Companies will suffer a drastic drop in profits and will have to restructure. This chain of events will cause global consumer spending to tank. Capacity for supplying goods will diminish as supply chains are fractured, there will also be inflation in certain sectors that are unable to cope with sudden demand, such as food and pharmaceuticals.

Countries will likely provide emergency loans to companies affected. These companies will meet maintain cash flow through debt, not profits. This will only be a stopgap. Companies will see higher debt ratios as their sales fall, resulting in a build-up of negative energy that may spark a full-blown financial crisis.

With the above in mind, stock markets will likely continue its downward trajectory. Countries will probably respond to such events with fiscal stimulus and monetary easing. However, these stimuluses have been tried many times in the past, so the effect will be limited this time. As the real economy shrinks, higher leverage ratios may ultimately trigger a liquidity crisis like the crisis linked to the collapse of Lehman Brothers.

We must also be mindful of the fact that we are currently still only at the beginning of this crisis. In the case of the 2008 global financial crisis, it took one-and-a-half years for the collapse of a Bear Stearns hedge fund on July 31, 2007, to lead to the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers on September 15, 2008 and stock prices (S&P 500) hitting bottom on March 9, 2009.

If there is a liquidity crisis, massive relief measures will be rolled out to stem the crisis. Even so, these responses and relief measures will lead to a collapse of the global financial system and will dramatically transform the workings of the global economy. The need for a next-generation financial system will be urgently called for, and the world will seek out new growth fields.

The Chinese economy is facing whether it could overcome the so-called middle-income trap. If there is a liquidity shock, it will surely become impossible for China to escape the “trap”, and the country risk being left behind by the global economy. Chinese companies can be broadly divided into state-owned enterprises with low capital efficiency and private enterprises with high capital efficiency. Fundamentally, in order to revitalize the economy, China should liberalize its financial markets, allowing pressure from market forces to push out “zombie companies.” In times of recession, the country should nurture sound markets that facilitate the inflow of new money while disposing of bad debt in a transparent, appropriate manner.

However, this is far from the current state of affairs in China. Although this is partly due to capital regulations, China’s accounting system is opaque, and the Chinese government is heavily involved in private companies (through the requirement to set up Communist Party committees within). For these reasons, corporate decision-making is not necessarily aligned with sound economic reasoning. The Constitution champions the preservation of communist party rule. Therefore, China naturally prefers to implement symptomatic measures rather than painful reforms that may jeopardize the status-quo. There is a real possibility that the whole Chinese economy could turn into a colossal “zombie economy.” This situation would closely resemble the structure of Japan before the collapse of its bubble economy and the country’s steps thereafter. In the case of China, however, the economy is much larger, and the stagnation would last much longer.

The Spanish flu is often cited as an example when illustrating the economic impact of a pandemic. In March 1918, the first wave of the epidemic struck the U.S. and Europe. The second wave began in late autumn of the Northern Hemisphere and the third wave started in winter in early 1919. The National Institute of Infectious Diseases of Japan has presented a variety of estimates for the 1918-1919 Spanish flu. Estimates put the number of Spanish flu patients worldwide at approximately 500 million, 20%-30% or one-third of the global population. Estimates for the mortality rate are 2.5% or higher. Mortality numbers range between 40 million, 50 million and 100 million.

In “Evaluating the economic consequences of avian influenza,” a research paper published by the World Bank, simulating the economic impact of pandemics of mild, moderate and severe scenarios. The severe scenario was based on the 1918-1919 Spanish flu. The simulation found that a severe pandemic would result in a “4.8% loss in GDP.” This impact is seen as the consensus. Indexing the adverse impact on the economy at 100%, the impact from mortality would be 13%, the impact from lowered productivity would be 29%, and the impact from reduced consumption would be 61%, indicating significant indirect impact. It was assumed in the first year of the pandemic, air travel would decline by 20%. Tourism, restaurant meals, and usage of mass transportation services would also decline by 20%.

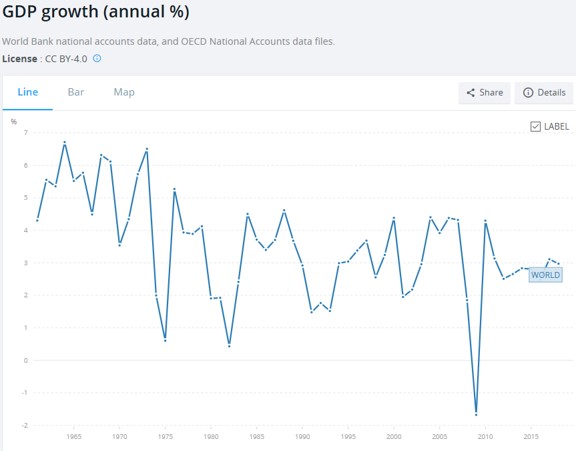

Compared to when the Spanish flu existed, we need to consider that global supply chains have increased in terms of size and complexity. The integration of financial markets has also advanced much further. Consequently, there has been a continuing convergence in the economic growth rates of various countries. This illustrates the difficulty of decoupling economies around the world.

Due partly to constraints on the availability of economic data, it would be impractical to directly compare the current global supply chain size with those of the Spanish flu. For example, trade volume as a percentage of global GDP has increased from around 30% back then to around 60% at present. Treating this as a proxy variable, we can estimate that the economic impact of a pandemic today could double in severity. If there were a pandemic like the Spanish flu of 1918-1919 today, it would not be surprising for such a pandemic to reduce economic output by around 10% of GDP.

Meanwhile, we can see that the quality of medical care has improved compared to the past. Back then, there was the Great War, and it is generally noted that people suffered from malnourishment. It is also true that medical care was much different at the time, penicillin not yet developed. If the mortality rate of COVID-19 turns out to be just over 1%, the world may get by with an economic impact mostly on par with that of the Spanish flu.

However, COVID-19 will still have a catastrophic impact on the economy. The global financial crisis was notable for the “instant evaporation of demand caused by a financial crunch.” In contrast, the global economy in a COVID-19 pandemic will have to be continuously fearful of an “unseen enemy,” leading to the prospects of a long-term pullback in market sentiment. Since 1961, the lowest global economic growth rate that has ever been recorded was negative 1.7% at the time of the global financial crisis. If COVID-19 has already entered a pandemic phase, there is a high likelihood that the economic growth rate may fall below what was recorded during the global financial crisis.

(This piece was written based on discussions held in the FISCO Global Financial and Economic Scenario Analysis Meeting, March 3, 2020)

カテゴリー

最近の投稿

- 人民元の国際化

- Old Wine in a New Bottle? When Economic Integration Meets Security Alignment: Rethinking China’s Taiwan Policy in the “15th Five-Year Plan”

- イラン「ホルムズ海峡通行、中露には許可」

- なぜ全人代で李強首相は「覇権主義と強権政治に断固反対」を読み飛ばしたのか?

- From Energy to Strategic Nodes: Rethinking China’s Geopolitical Space in an Era of Geoeconomic Competition

- イラン爆撃により中国はダメージを受けるのか?

- Internationalizing the Renminbi

- 習近平の思惑_その3 「高市発言」を見せしめとして日本叩きを徹底し、台湾問題への介入を阻止する

- 習近平の思惑_その2 台湾への武器販売を躊躇するトランプ、相互関税違法判決で譲歩加速か

- 習近平の思惑_その1 「対高市エール投稿」により対中ディールで失点し、習近平に譲歩するトランプ